Rauika Editor, Reverend Blythe Cody, shares her thoughts on feminism and the new Barbie movie.

The release of the Barbie movie has generated a flurry of discussion around patriarchy, feminism, and what it means to be a liberated modern woman. The film’s Director, Greta Gerwig, views her creation as a feminist film, describing its feminist perspective as “Looking at all the thorniness and stepping into what is the negotiation of what women need to be, and how to give them something other than a tightrope to walk on, is how it feels feminist to me.” The film has been praised by many as a triumph for feminism and women’s liberation. A review of the film by Maressa Brown in Parents Magazine described the Barbie movie as ‘…anything but a fluffy, two-hour commercial for a doll. It’s bursting with feminist ideas and themes that, with hope, will spur exciting, educational conversations between parents and kids about why we don’t live in a world in which women have as much power as they do in Barbieland—and why it is a problem for anyone, no matter their gender, to be made to feel like an accessory, and more.’

Feminist ideas and themes, however, are not the simple or straightforward path toward liberation for all women that the above might imply.

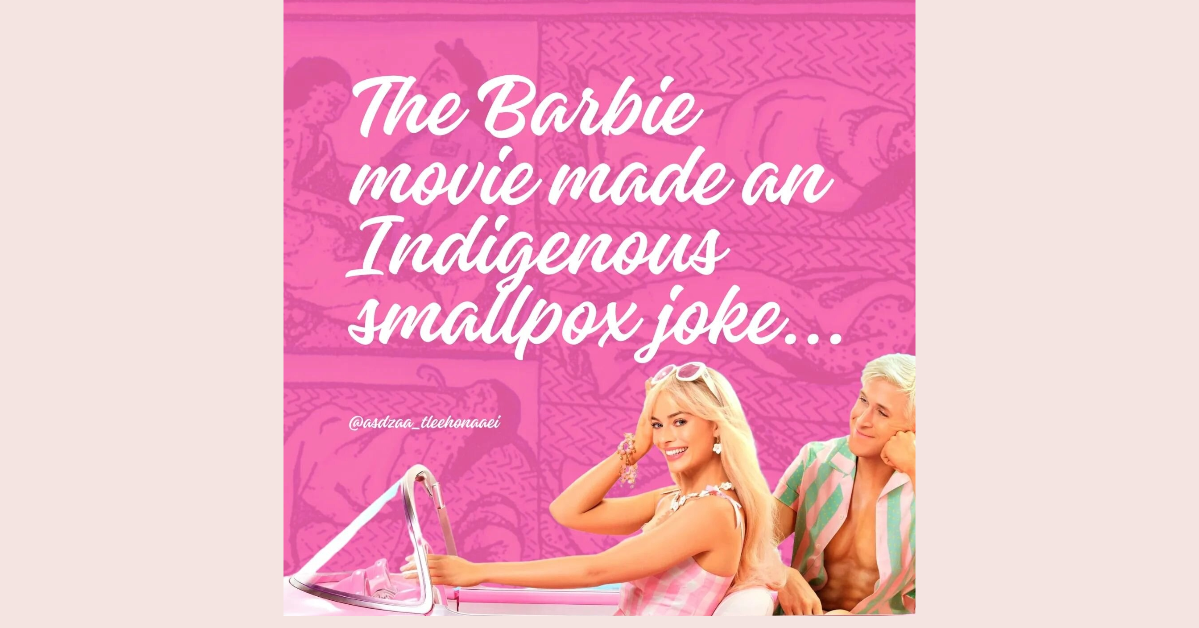

Indigenous journalist Anna McKenzie, a member of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation, wrote the following account of her experience watching the film:

‘We were enjoying the movie, and there was a lot of laughter. Just what I needed to set my heart and mind straight before a busy week. And then, mid-movie, as Barbie prepares to leave “Barbie Land” to go to the “real world,” the character Gloria (played by America Ferrera) makes a comment that catches me off guard.

“Oh my god! This is like in the 1500s with the Indigenous people and smallpox,” she says. “They had no defences against it!”

Wait – what did she just say?

I pause and look to my friend. Did the Barbie film just compare women and patriarchy to Indigenous people and disease? Was that really necessary? The thoughtless line about Indigenous people and smallpox ironically comes right before an insightful and impassioned monologue by Ferrera’s character on how complicated it is to be a modern-day woman.’

There is a feminism that fails to see how it is complicit in the very disempowering agendas that it hopes to dismantle. Shahed Ezaydi writes, ‘…an important thing to note about the term ‘white feminism’ is that it’s not referring to a particular group of people but rather acknowledges a particular system and ideology in place in the world of feminism…white feminism can be practised and asserted by anyone regardless of their racial identity… this is an approach to gender equality that ultimately asks you to aspire to whiteness and not equal rights. The more we can all break it down and understand the ins and outs of white feminism and the harms it can cause to so many communities, the more we can focus our energies on women’s liberation as a collective that prioritises care and compassion for all.’

Which requires us to ask, what kind of liberation for women are we as a Church striving toward?